Chosen Equal

It is no accident that both America and Israel define their ideals in a Declaration of Independence that invokes trust in a God that the Hebrew framers called “the Rock of Israel.”

Few historians are better suited to host an anthology on the Jewish Roots of American Liberty than Hillsdale University professor Wilfred M. McClay, beloved author of Land of Hope: An Invitation to the Great American Story, just issued in a second edition alongside a Student’s Handbook. That highly popular textbook – astonishingly, no oxymoron – tells the tale of feisty and faithful people who shared the vision of Judaism, which Sir Jonathan Sacks, former Chief Rabbi of the United Kingdom, defined as “the voice of hope in the conversation of humankind.” The same message is conveyed anew in this newly published collection of twenty-one engaging articles based on a series of programs on “Restoring the American Story.” In McClay’s words, together they seek to demonstrate “the closeness and foundational character of the relationship between the American experience and the Jewish experience, and the nature of the Hebraic impact on the United States.” Or as Rabbi Sacks once put it: “Israel, ancient and modern, and the United States are the two supreme examples of societies constructed in conscious pursuit of an idea.”

Two decades ago, a similar message inspired the seminal anthology gathered by another great scholar, the venerated late president of Religion and Public Life Institute and editor of First Things, Rev. Richard John Neuhaus. Titled The Chosen People in an Almost Chosen Nation: Jews and Judaism in America, it too sought to remind readers of the intimate relationship between the founding traditions of what is generally known as Western Civilization. Notwithstanding differences among - and within - these two religious communities on nearly every subject, they share a fundamental commitment to human thriving guided by a higher light that makes those very differences possible, indeed necessary, reflecting the essential roots of liberty.

Standing athwart the escalating antisemitism and anti-Americanism on America’s campuses today, this anthology affirms, in McClay's eloquent summation, America’s

profound and incalculable debt to the Jews. It is they who provided the deep metaphysical, moral, and anthropological foundation upon which much of the American experiment in democratic self-government was erected, and who have gone on to contribute in ways large and small to the soul of America, and its making and improving.

Respectful of divergent views but intolerant of lies, the book will equally inform and inspire.

To explain why teaching American history in faith-based schools, whose enrollments have grown exponentially in the past couple of years, McClay appeals to the most profound observer of America’s national culture, Alexis de Tocqueville. Finding it “exceptional,” Tocqueville was equally stunned by the ubiquity of regular church attendance as by the harmony and plurality of sects. He concluded that religious observance was the essential feature of American democratic life: “the first of [its] political institutions.”

The country’s titular Father would have wholeheartedly agreed. In his iconic 1796 Farewell Address, George Washington had declared that “of all the dispositions and habits which lead to political prosperity, Religion and morality are indispensable supports.” McClay adds that the first President spoke for “countless others from John Adams, Benjamin Rush, John Jay, and more” - notably, I might add, Alexander Hamilton, the only founder educated at a Yeshiva and coincidentally the Address’s ghostwriter. John Adams, for example, expressed in a personal letter written in 1818 that “man is constitutionally, essentially and unchangeably a religious animal. Neither philosophers nor politicians can ever govern him any other way.”

Political prosperity refers to the inexorable connection between material flourishing and personal agency, enveloped in John Locke’s trinity of life, liberty, and property. While the latter was rhetorically, though not substantively, translated by Thomas Jefferson into “the pursuit of happiness,” all the founders reflected the conviction McClay describes as the need for “sources of moral authority that transcend the state and are capable of holding the state accountable to a standard higher than itself.” This implies a pluralistic approach to religion “as a source of moral order and social cohesion.” That the Founders knew of Locke’s profound debt to Hebraic tradition seems undeniable.

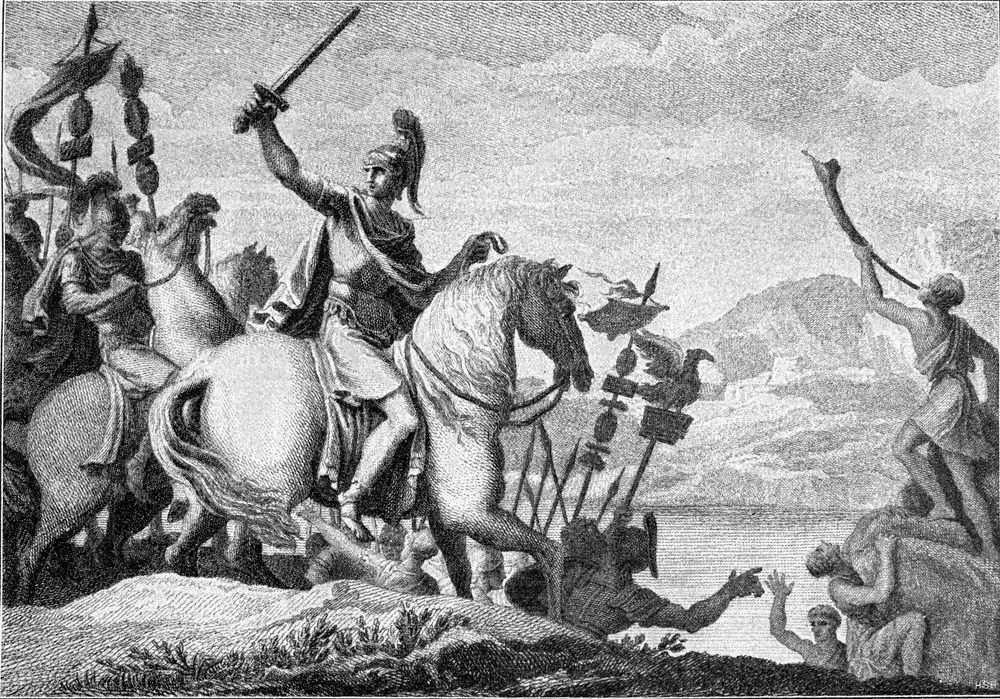

But what aspects of religion lie at the core of morality in a covenantal community uncompromisingly committed to freedom of thought? The key lies in the profoundly personal biblical spirituality that was revolutionizing the Anglo-Saxon world, which Rabbi Dr. Dov Lerner credits to John Milton’s incomparable, towering talent. Through literary masterpieces such as Paradise Lost, Milton succeeded in replacing the Greco-Roman view of human success, based mainly on battle prowess and conquering external enemies, with the far deeper Abrahamic requirement of conquering one’s inner self.

The political implications were not long in coming, as the condescending King Charles I categorically refused Parliament’s attempts to curb his arrogant abuse of power. By then, the traditional assumptions that the British monarchy alone could cement the moral order and that socio-economic equilibrium demanded acceptance of natural class hierarchies had been sorely fraying. When the Puritan military leader and Parliamentarian Oliver Cromwell, later selected as the British territories’ first non-Royal Lord Protector, asked Milton to defend regicide, the poet wrote that people “need not Kings to make them happy, but are the architects of their own happiness.” Political institutions, he firmly believed, should give each person the ability to cultivate the paradise within, guided by a higher light.

So too did the plainspoken Benjamin Franklin, who suggested this motto for the Great Seal of the United States: “Rebellion to tyrants is obedience to God.” It was to grace a picture of Moses parting the Red Sea. Though uncompromisingly radical and, much to Abigail Adams’s consternation, hardly a Puritan, Franklin was skeptical of state overreach in a manner fully consistent with the ancient biblical tradition.

Freedom of conscience was so crucial to the founding generation, writes Dr. Mark David Hall, that “it was common for it to be referred to as a ‘sacred right.’” Thus, when President James Madison called Congress to prayer on July 23, 1813, he explained that he sought to connect the “sacred rights of conscience” to our “present happiness” and “future hopes.” Hall similarly cites George Washington’s letter to the Newport Hebrew Congregation in Rhode Island, written on August 18, 1790, which attests to the complete synchrony of the Jewish and American traditions: “May the Children of the Stock of Abraham, who dwell in this land, to continue to merit and enjoy the good will of the other Inhabitants; while every one [sic] shall sit in safety under his own vine and figtree, and there shall be none to make him afraid.”

The President’s equally affectionate letter to the Hebrew Congregation in Savannah, Georgia, of June 14, 1790, is actually a message to all Americans:

May the same wonder-working Deity, who long since delivering the Hebrews from their Egyptian Oppressors planted them in the promised land – whose providential agency has lately been conspicuous in establishing these United States as an independent nation – still continue to water them with the dews of Heaven and to make the inhabitants of every denomination to participate in the temporal and spiritual blessings of that people whose God is Jehovah.

Savannah’s storied Mickve Israel congregation, established in 1735, was also the fortunate recipient of letters from James Madison, who had praised the “perfect equality of rights” that the United States secured “for every religious sect,” and from Thomas Jefferson, who wrote that America proved that “religious freedom is the most effectual anodyne against religious dissention [sic],” adding that he even hoped Jews would one day take their seats “at the board.” Currently, 32 members of Congress, no fewer than 6 percent, are Jews. That the Old Testament provides the quintessential narrative of covenantal nationhood is widely known. But it takes a scholar like Dr. Daniel Dreisbach to document how Jewish practice, too, was emulated by the founders:

The theme that America was analogous to the Hebrew nation and that the newly independent states should emulate the Hebrew commonwealth’s ‘republican’ form of government was developed in political tracts and sermons, and even in various deliberative bodies.

In his influential sermon to Massachusetts’s highest public officials in 1775, for instance, Harvard’s president, Samuel Langdon, praised “[t]he Jewish government, according to the original constitution which was Divinely established,” for being “a perfect Republic” in vital respects.

Similarly, Roger Sherman of Connecticut urged his fellow Constitution-drafters to consult their bibles “and duly weigh and consider the civil polity of the Hebrews, which was planned by Divine Wisdom, for the government of that people although their territory was small; … [and] their laws were few and simple.” He then adds that “their processes were neither lengthy nor expensive”! Proof that Yiddishe frugality meets Yankee common sense.

For the founders, pragmatism naturally complemented morality. But morality, above all, demands truth, trust, and solid oaths. Any state whose culture degenerates into skepticism and nihilism cannot last long without descending into Hobbesian chaos. A liberal republic whose legitimacy rests on the self-evident right to liberty to be enjoyed, in principle, by every human being can only be sustained by a constituency that respects this basic principle as sacrosanct. This is why oath-taking is defined in the Constitution as a solemn appeal to the Supreme Being as the ultimate, albeit unseen, witness. To this day, the last phrase of an official oath is: “So help me God.”

But what if the swearer no longer believes in the meaning of that phrase? Are Americans drowning in a sea of irreligion? Is the CEO of the Tikvah Fund, Eric Cohen, right to deplore, alongside former Attorney General William Barr, that our culture is all but “broken”? On October 17, 2019, Barr had declared our culture to be descending into “chaos” and despair. Like him, Cohen finds that “anti-Biblical civilization is now on the offensive,” as modern science is invoked by progressive self-styled prophets of scientism who consider religious morality “oppressive, judgmental, and unnecessarily prohibitive.” In place of the Ten Commandments, they offer “amoral niceness,” as “a well-policed moral relativism is now our dominant ideology.”

Moral relativism is, in fact, no morality at all. Without a standard of order, without a sense that existence has a meaning, how can it be deemed worth living? Wilfred McClay returns to Nathaniel Hawthorne, whom he describes as “partly a romantic, [though] even more of a Hebrew prophet.” He marvels at the erudite, introverted novelist’s premonition of future despair, since “technological progress is worse than an illusion. For it can never instruct us how to live, or what we should live, let alone die, for. Alongside God, the theocidal secularist slays his own reason for hope, for life, for love.”

Where would literature, music, and art be without biblical imagery to capture some of the nation’s most dramatic moments? The citation inscribed upon the Liberty Bell, “Proclaim liberty throughout all the land,” invoked again at the Liberty Jubilee in 1876, after passage of the Civil War amendments righting the wrong of slavery, for example, comes from Leviticus. It would be revived again in a replica of the Bell by the Union of Jewish Orthodox Congregations in 1926, in transliterated Hebrew.

But especially poignant are such characters as Esther, Samson, Daniel, Hagar, Moses, and Elijah, among others, most masterfully captured by co-editor Rabbi Stuart Halpern of Yeshiva University. Symbols of timeless archetypes of courage and faith, each represents pain, loss, often excruciating choices, but also transcendence and sometimes ecstasy, with an intimacy comparable to the shared memory of family. But tragically, the Judeo-Christian tradition is gradually being torn asunder in unprecedented ways. While the Jews emerged from the ashes of near-annihilation by Nazis and their acolytes with greater self-confidence than ever, Israel having been miraculously reborn after two millennia, America’s best and brightest, or at least its most credentialed elite, turned against their own legacy with a self-loathing bordering on the pathological.

They seem “driven by the fierce belief that America has never been a nation dedicated to a great idea,” laments Rabbi Meir Soloveichik. Although most ordinary folk are still solidly behind Israel, too many self-styled “woke progressives hate Israel because they hate America; they work, above all, to undermine the notion that America can consider itself a covenantal nation, and they therefore hate the embodiment of the original covenantal nation.” By undermining the biblical tradition, they fuel hatred not only of Israel and of the Jewish people but of liberty as the founders understood it. Antisemitism, antizionism, and anti-Americanism constitute the unholy trinity of our time.

Where better to turn for inspiration than to the generous dedication of the beautiful new building of the Jewish Community Center in Washington, DC, on May 3, 1925, by the underestimated, exceptional president Calvin Coolidge. Recalling how the story of Exodus inspired the founders, Coolidge expressed his admiration for “[t]he Jewish faith [which] is predominantly the faith of liberty.” He went on to thank American Jews for

they have always come to us, eager to adapt themselves to our institutions, to thrive under the influence of liberty, to take their full part as citizens in building and sustaining the nation, and to bear their part in its defense, in order to make a contribution to the national life, fully worthy of the traditions they had inherited.

Today, no other nation on earth is closer allied with America than Israel. It is no accident that both define their ideals in a Declaration of Independence that invokes trust in a God that the Hebrew framers called “the Rock of Israel” and the Jeffersonian drafters called “Divine Providence,” who created mankind, male and female, in His own image. Exactly one century later, the words of “silent Cal” still ring with both the clarity of Boston’s Bell of Liberty and the heart-wrenching but hopeful howl of the shofar.

Juliana Geran Pilon is Senior Fellow at the Alexander Hamilton Institute for the Study of Western Civilization. Her latest book, An Idea Betrayed: Jews, Liberalism, and the American Left, has just been published.

Prosecuting Maduro

Much has been said about the expedient capture of Nicolas Maduro by American forces. Prosecuting him will not be so straightforward.

Peru: Between Chinese and American Influence

The U.S. government recently announced that it will designate Peru as a non-NATO military partner.

California’s EU Style Regulatory Gambit

While the EU is trying to be the globe’s regulator, California is trying to play the same role over the rest of the U.S.

Get the Civitas Outlook daily digest, plus new research and events.