Nicolás’ Last Dance

If Maduro’s era was defined by spectacle and defiance, the next chapter, should it materialize, will be judged not by dances but by institutions.

Editor's Note: This essay is part of our Venezuela Symposium.

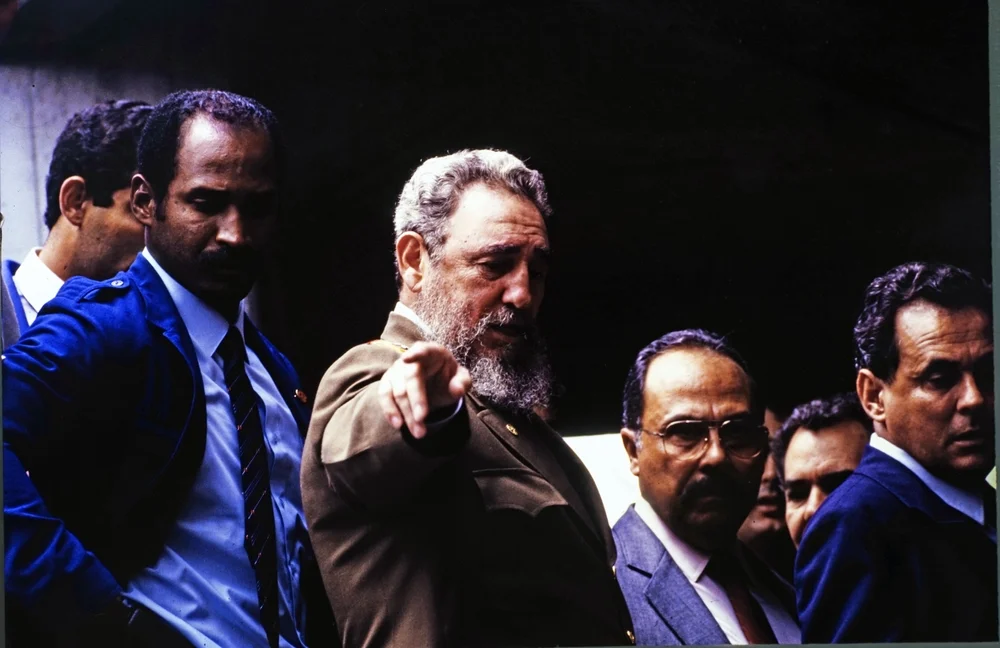

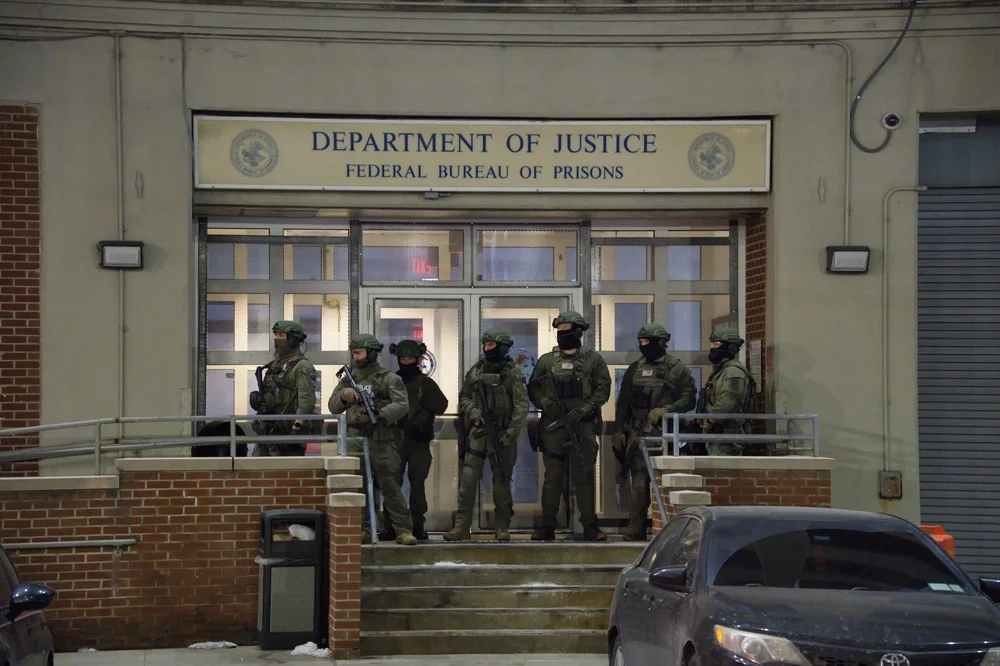

After several months of mutual threats between U.S. President Donald Trump and then Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro Moros, the world was stunned on January 3rd. Maduro and his wife, Cilia Flores, were arrested and transferred to New York City following an indictment accusing them of leading a terrorist and drug-trafficking organization known as El Cártel de los Soles.

Throughout those months of escalating rhetoric, Maduro responded with mockery, frequently resorting to televised dances that many interpreted as deliberate provocations. Eventually, Trump carried out his threat.

Maduro’s arrest ended — at least symbolically — almost 27 years of Chavismo, the political regime founded by former army officer and President Hugo Rafael Chávez Frías, who died in 2013. This movement maintained particularly close ties with Argentine Kirchnerism, a left-wing political formation that emerged from a reconfigured strand of Peronism. Under Maduro’s tenure, Chavismo accumulated a substantial record of human-rights violations allegations, including accusations issued by a few organizations and figures traditionally sympathetic to the regime.

Among the most significant were the so-called Bachelet Reports, issued between 2019 and 2022 by a team led by former Chilean President Michelle Bachelet, which documented the neutralization of political opposition, enforced disappearances, sexual violence, summary executions, and systematic interference with humanitarian missions. Yet despite mounting international pressure, Maduro continued to attract the support of left-leaning parties and organizations worldwide — often deflecting criticism with another dance, another performance.

The irony is difficult to ignore. Both Chavismo and Argentine Kirchnerism received explicit backing from organizations such as the Madres de Plaza de Mayo, whose moral authority was built upon denouncing the atrocities committed during Argentina’s Proceso de Reorganización Nacional, one of the most brutal dictatorships in Latin America during the 1970s. From an economic standpoint, Venezuela holds some of the world's largest oil reserves. This abundance enabled Chávez to lend former Argentine President Néstor Kirchner the funds needed to cancel Argentina’s IMF debt, thereby avoiding external audits of fiscal policy and public spending. The transaction, however, was far from altruistic: interest rates reportedly tripled the original debt.

Despite its extraordinary natural wealth, Venezuela today has one of the poorest populations in the region. Once among the countries with the highest per-capita GDP in Latin America, its economy collapsed over the last decade, placing it among the lowest. Maduro once again danced his way through international scrutiny, attributing inflation and currency devaluation to foreign actors — particularly the United States.

Against this backdrop, it is hardly surprising that nearly 30 percent of Venezuela’s population — approximately eight million people — has emigrated over the past decade, fleeing persecution, economic collapse, and hunger. When doubts about Venezuela’s democratic credentials intensified, elections were held, while opposition leaders with genuine chances of victory were systematically arrested or barred from running.

In the 2024 elections, Maduro once again navigated allegations of fraud and retained the backing of left-wing governments, parties, and organizations worldwide. Unbeknownst to him, it was his last dance.

The fall of Maduro — whether abrupt or negotiated — would likely mark a profound turning point in Argentina–Venezuela relations. In a post-Maduro scenario, the bilateral relationship would almost certainly undergo a process of institutional normalization, driven less by ideological affinity and more by pragmatic considerations.

For Argentina, a transition in Venezuela would remove a longstanding source of regional and international diplomatic tension. If they wish to be taken seriously, future Argentine governments —regardless of political orientation — should recalibrate their stance, prioritizing respect for democratic institutions, human rights, and international commitments over the ideological solidarity that characterized earlier decades.

From Venezuela’s perspective, re-engagement with Argentina could form part of a broader effort to reintegrate into regional and global financial systems. Argentina’s experience with debt restructuring, IMF negotiations, and post-crisis institutional rebuilding may become a reference point—though not a model—for Venezuelan policymakers seeking legitimacy and economic stabilization.

However, the legacy of Chavismo will not disappear overnight. Mutual distrust, unresolved legal disputes, and the humanitarian consequences of mass migration will continue to shape bilateral relations. Any sustainable rapprochement will depend on transparent democratic processes in Venezuela and a deliberate shift toward rule-based diplomacy on both sides.

If Maduro’s era was defined by spectacle and defiance, the next chapter, should it materialize, will be judged not by dances but by institutions.

Juan Martín Morando is a former judge and Professor of Law at Universidad Científica del Sur. Member of BeLatin.

The Venezuela Symposium

Eight Latin American contributors discuss Venezuela's future and its wider consequences for the region.

Venezuela Post-Maduro

Indeed, for many, the Venezuelan situation seemed to have no other way out, since everything had already been tried without success. It was about time.

Donald Trump's New Hemispheric Policy

By adopting a more assertive foreign policy, the administration sought to reposition the United States at the center of the regional order.

Get the Civitas Outlook daily digest, plus new research and events.