Slavery in Latin America in the Twenty First Century

Venezuela now faces a historic opportunity, and one can hope that Colombia, Cuba, and Mexico may soon face the same.

Editor's Note: This essay is part of our Venezuela Symposium.

Is it possible to compare a dictatorship with slavery? Both systems involve the deprivation of liberty and human rights and are based on oppression and absolute control. When dictatorships also lead to narco-governments, their effects transcend borders: not only do they dominate territories, but they also seek to enslave people through drug dependence on extremely powerful drugs such as fentanyl. This approach can be analyzed in terms of three reflections.

The Law and Its Distance from Reality

Historically, the law has persistently lagged reality. For centuries, legal systems not only tolerated but also legitimized slavery. In the early colonial period (1607-1783), owning slaves was perfectly legal. In 1640, John Punch was sentenced by a judge in the Colony of Virginia to slavery for life: it was the law itself that made a man a slave.

Paradoxically, many slaves obtained their freedom not by law but by buying it or appealing to their owners' will, as happened with Aesop. The abolition of slavery was not the work of the judiciary, but of political leadership and profound historical changes. The Thirteenth Amendment was a direct result of the Civil War and the political leadership of Abraham Lincoln, among others, rather than a spontaneous evolution of the law.

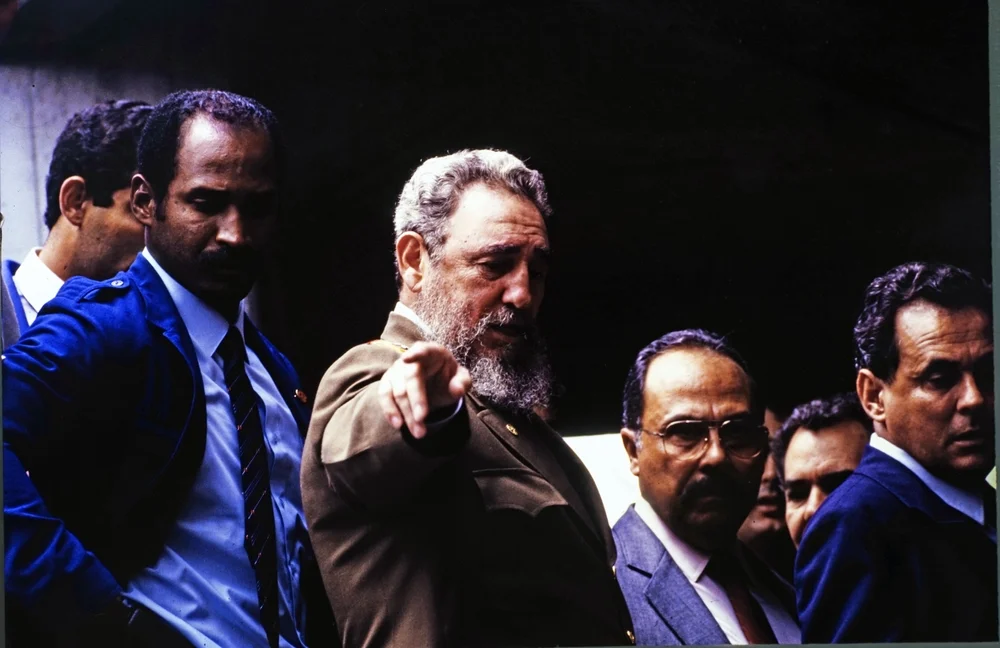

This lesson is key to understanding contemporary dictatorships. Many regimes in Latin America have enslaved millions of people in a modern way, causing mass migrations, strengthening drug trafficking, and seriously affecting investment and foreign trade, all with the ultimate goal of enriching dictators in power.

The case of Venezuela is illustrative: in 27 years under the governments of Chávez and Maduro, more than 27 percent of the population emigrated. Three out of ten Venezuelans fled the country. Historically, about one in ten Mexican citizens has emigrated to the United States, representing more than 12 million people. As in the nineteenth century, profound changes today require firm leadership and bold decisions in the face of oppressive terrorist regimes.

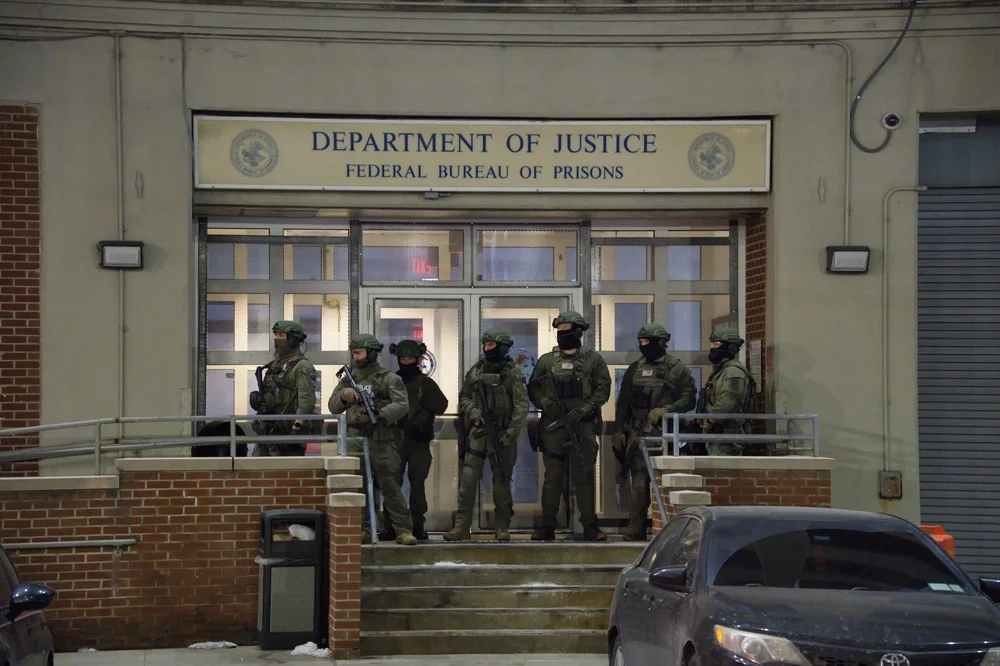

The Arrest of Maduro as an Act of Liberation

Until recently, international law seemed to protect figures such as Maduro, under the principle of non-intervention in the internal affairs of states, enshrined in the UN General Assembly Resolution 2131 (XX) of 1965. However, this protection only applies to truly sovereign and independent states.

Sovereignty emanates from the people. The elections held in Venezuela in 2024 were neither free nor fair; power was retained by force, stripping the Venezuelan people of their sovereignty. In this context, there can be no talk of a sovereign state. Maduro´s arrest does not constitute an invasion, but the arrest of a narco-dictator who lost all legitimacy. In addition, experts such as John C. Yoo have renewed their support for these actions, demonstrating that they are constitutional under U.S. law.

Mexico faces a similar threat today. An electoral reform scheduled for approval in mid-January 2026, according to specialists, would guarantee the indefinite permanence of the ruling party in power, annulling any real competition. Jose Woldenberg, Luis Carlos Ugalde, and Lorenzo Córdova (each a former president of Mexico's National Electoral Institute (IFE/INE), the agency responsible for administering free elections for over three decades) have persuasively argued that the proposed electoral reform constitutes a regression toward authoritarianism. They contend the reform centralizes political control and creates conditions for increased penetration of organized crime into electoral processes, characterizing it as one of the gravest threats to Mexican democracy.

Consistent with these concerns, the Partido Verde and the Partido del Trabajo, both allied with Morena, have publicly rejected the reform, asserting that it endangers their political viability and financial survival. Taken together, these critiques indicate that the reform advances Morena's project to exert de facto hegemony over electoral administration and outcomes.

With this 2025 electoral reform, Mexico would risk ceasing to be a sovereign nation. Although it is formally called a Republic, the division of powers has been severely eroded, and the judiciary is captured by an executive branch incapable of containing organized crime. Mexico is already one of the most dangerous countries in the world to live in.

The Domino Effect in Latin America

The impact will not stop in Venezuela. Colombia, Cuba, and Mexico also face critical questions about their futures. Colombia faces the growing weight of the cartels, and its stability is increasingly fragile.

Cuba could collapse without military intervention, simply because of the lack of resources after the end of the Venezuelan subsidies. However, recent reports from January 2026 indicate that Mexico continues to supply Cuba with substantial shipments of crude oil and refined fuels, transacted through the state-owned subsidiary Gasolinas del Bienestar. These shipments, often worth millions, have been criticized for supporting the Cuban regime and generating tension with the U.S.

Mexico represents the most delicate case. The danger and productive capacity of Mexican cartels far exceed that of other countries, with documented links to high-level political actors. Added to this are legal reforms that have generated alarm among U.S. investors, just as the renegotiation of the USMCA approaches.

The Trump administration has demonstrated that meaningful change does not require the costs of an invasion. President Trump is unlikely to halt his course in Latin America given his convictions about the region and immense presidential powers.

Venezuela now faces a historic opportunity, and one can hope that Colombia, Cuba, and Mexico may soon face the same. “America first” has sparked a wave of hope. May the peoples of these troubled nations find peace, prosperity, and the common good.

Raul Howe is Executive Director of BeLatin, Fellow in Public Law and Policy, Berkeley Law, University of California, Berkeley.

The Venezuela Symposium

Eight Latin American contributors discuss Venezuela's future and its wider consequences for the region.

Venezuela Post-Maduro

Indeed, for many, the Venezuelan situation seemed to have no other way out, since everything had already been tried without success. It was about time.

Donald Trump's New Hemispheric Policy

By adopting a more assertive foreign policy, the administration sought to reposition the United States at the center of the regional order.

Get the Civitas Outlook daily digest, plus new research and events.