The Significance of “Getting Cheaper” Efficiency

By focusing on the notion of efficiency in a way that an engineer, rather than an economist, would address the problem, Potter has presented a fresh and engaging set of tools for understanding some of the core trends of the last one hundred years.

Potter motivates the book with a simple question that yields many complex answers. The question is “why do products get cheaper?” He calls this process of “getting cheaper” efficiency.

The impressive thing about this book is that Potter takes the concept of efficiency, which is central to much of microeconomic analysis, and asks the question that economists never ask: how do processes become more efficient? The economist answer is “something something competition something,” but academics simply assume the underlying activities without ever considering how they work.

There are really two questions: The first is “How do producers figure out their cost of production?” The notion of a “supply curve” assumes that the problem has been solved. As Potter points out, there is no one answer, and actual market participants are constantly groping and making marginal improvements. The very idea of a “supply curve” is nonsense, at least in terms of firm decision-making.

The second question is, “Why do costs of many (but not all) products fall over time?” It’s true: the history of commercial society is a near-constant fall in costs, and ultimately in prices. This is true even in many commodities, as Paul Sabin’s 2014 book The Bet, about a wager between Paul Ehrlich and Julian Simon, illustrates. But the phenomenon of falling prices for most consumer goods, adjusting for quality improvements, is quite general. Why would that be true, given that the goal of greedy corporations is to raise prices?

Potter’s core claim is that improving production efficiency — producing goods and services in less time, with less labor and fewer resources — is one of the main engines behind what Deirdre McCloskey calls “the great enrichment.” But the notion (popular among economists) that “increased human capital” or “technology” explains falling costs is vague and actually misleading. Potter claims that there are specific “levers” that producers use to reduce costs, and that much of the explanation for why it works in some areas (phones, televisions, drugs, computer components) and not in others (construction, health care, education) has to do with physics and fundamental facts about production.

The book's general contribution, then, is to identify the five levers (changing production methods, exploiting scale economies, lowering input costs, eliminating steps, and tightening process control and precision) and then to examine specific examples of where this worked and where it didn’t.

Potter opens with the penicillin story, and one can see why. The miracle of penicillin is almost always told as a combination of lone genius (Fleming) and serendipity (what’s this in my petri dish?). Potter notes that the actual miracle was the development of a manufacturing process that allowed cheap, consistently potent penicillin to be universally available. The drug only mattered once people figured out how to grow the mold at scale (corn steep liquor as a cheap medium, submerged fermentation, better strains, process control), which turned a lab curiosity into a mass-produced “miracle drug” and cut battlefield infection deaths by roughly three-quarters.

As discussed above, cost reductions and commercial viability are not inevitable; in fact, a focus on the claim that prices of long-lived products consistently fall is an example of survivor bias. The only reason that we use a product long enough for the “levers” to come into operation is that no better or cheaper substitute has eliminated that product from the market. Potter defines a production process as a sequence of steps that transforms inputs into outputs over time, consuming labor, materials, energy, and capital equipment.

With that caveat, it makes sense to accept Potter’s formulation: efficiency is the process of constantly and incrementally changing manufacturing practices, rarely just “sprinkling technology” on top of the way economic growth models often portray things.

A significant part of the book's value lies in its examples. Under the “new processes” lever, Potter considers the shift from older ironmaking methods to the Bessemer process, and subsequently to later refinements, which radically reduced the time and energy required to produce a ton of steel. Of course, cheaper steel is a force multiplier on price reductions, since so many other manufacturing processes use steel in machinery and in the products themselves. And, in a process akin to, but not as dramatic as, the development of penicillin, process innovations in pharmaceuticals and chemicals transformed small-batch laboratory recipes into industrial continuous processes. The useful thing about both examples is that there was no improvement in the product per se — steel and drugs were available early on, but were very expensive — but rather the development of commercial viability that changed the world.

The “cheaper inputs” lever is partly process development and partly a reduction in transaction costs arising from optimizing the balance between vertical integration and spot-market flexibility in supply chains. The economies of scale avenue for cost reduction is deceptive because the very investments that reduce per unit costs are the most likely to be wasted if a nimble ability to change products and update functions is required. Potter effectively describes how the “Model T” illustrates both sides of the dilemma. The Ford production line was so dialed in that the cost of Model T fell dramatically. The 1911 Runabout cost $680; in 1924, the price was $260, a 75 percent decline in nominal terms. Economies of scale, rah!

But in 1926, Ford decided it needed to switch models and update to the Model A. They had to close the factory for more than six months, and the combination of lost sales and retooling cost the company the equivalent of $2 billion (in 2024 dollars).

This means that economies of scale are more likely to be exploited in commodity industries such as steel; for most complex consumer products of the twenty-first century, pursuing scale economies is extremely risky.

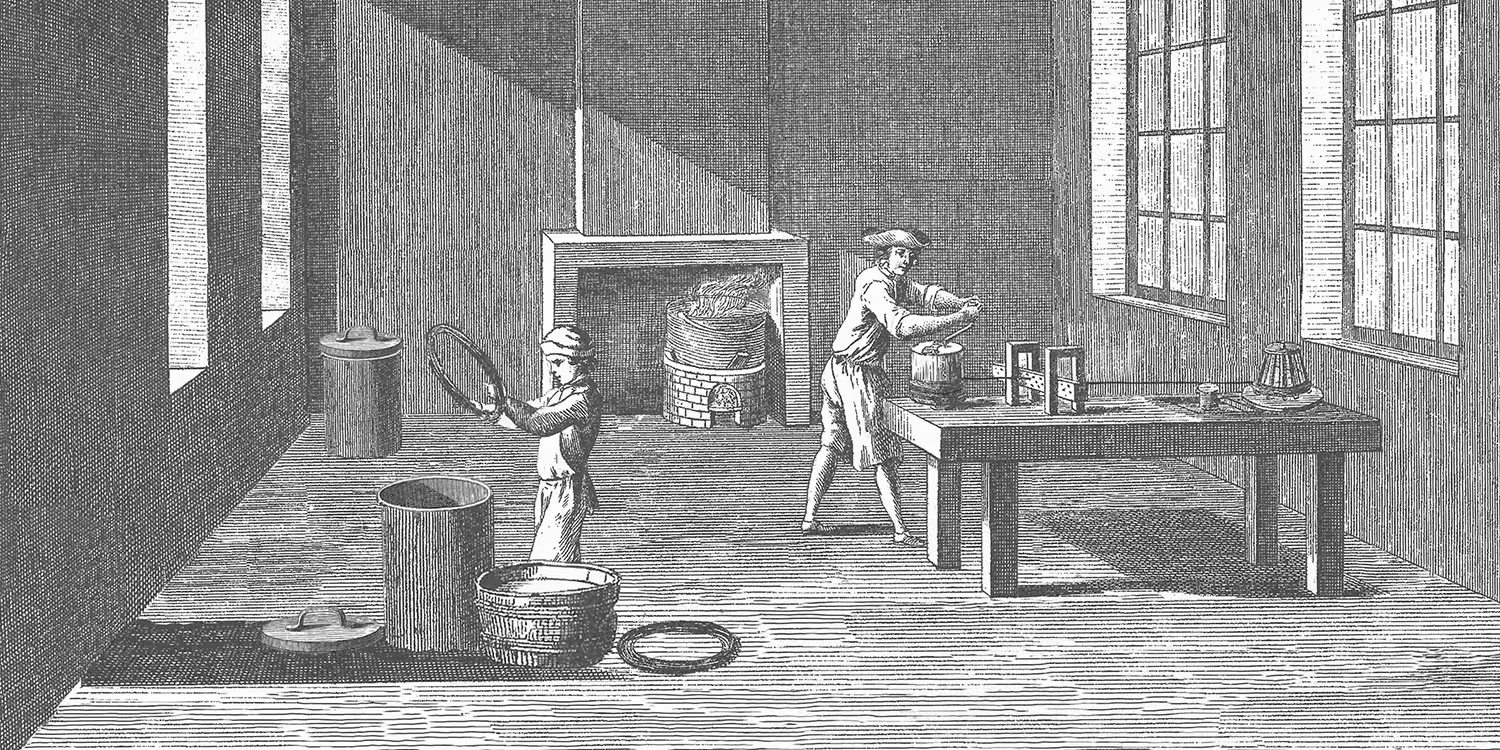

Potter likewise documents the nature of the other “levers” and provides examples that illustrate each clearly. Perhaps most interestingly, he takes up the “division of labor” explanation, made famous by Adam Smith’s “Pin Factory” example. Potter notes that while division of labor can reduce costs, it is necessary to match the resulting cost/output increase with an output market. The decline in cost is not automatic, and division of labor only works out if the situation allows it. Potter highlights the contributions of Charles Babbage, in his 1832 book On the Economy of Machinery and Manufactures, as having made this point most clearly. Most, and perhaps all, “process improvements” in a production line have upfront fixed costs that will only be justified if there’s a large enough production volume to spread them over. But that depends on how many of the units are likely to be sold, and the costs of storing excess inventory. Smith wasn’t wrong about division of labor, but (unsurprisingly) there were many later developments he had no way of predicting.

Potter concludes by noting that three of the most critical industries, in terms of how people live their lives, have proven almost impervious to the cost reductions that otherwise seem nearly universal. These industries—housing/construction, healthcare, and education—have remained constant or, in many cases, increased substantially in cost. (I was expecting Potter to mention the exception, which is laser eye surgery. This area of health care is closest to market provision, and in this one area, health care costs have actually fallen substantially, adjusting for inflation.)

He speculates about the reasons these areas stubbornly resist the general trend. Potter’s own experience with the failed Katerra modular housing startup is instructive. It turned out it was not enough to take the stick-built construction technology used for most housing, and “put it into a factory.” In some ways, it was the experience with the failure of Katerra, given that Potter had expected it to work well, that led him to want to write this book in the first place.

Overall, the book gives a very clear, “engineer’s-eye view” of efficiency as a set of concrete mechanisms, not a magic word, and it grounds that view in deep, readable case studies drawn from a wide range of industries. I tend to like this sort of precision and deeply considered examples, so the book worked for me on several levels.

On the other hand, both the difficulty of the discussion and the relentlessly optimistic account of efficiency don’t align with the views of many people that “everything is getting more expensive.” Of course, the common view is based on our recent period of inflation, with nominal prices increasing for almost everything. Potter considers the long-term secular decline in real prices, which is more important but harder to perceive.

I expect Potter’s response to such a criticism would be that he makes no pretense of saying the system is good or bad. By focusing on the notion of efficiency in a way that an engineer, rather than an economist, would address the problem, he has presented a fresh and engaging set of tools for understanding some of the core trends of the last one hundred years. The book is worth your time.

Michael Munger is Professor of Political Science and Economics at Duke University. His research focuses on the relations between political and commercial institutions.

Becoming All-American

Blue Moon takes place on the evening of March 31, 1943, the opening night of Oklahoma!

The Original Sin of U.S. Health Care

As long as most Americans receive health insurance as an invisible, employer-managed fringe benefit, health care will remain expensive, opaque, and unresponsive.

.jpeg)

The False Equivalence of Multicultural Day

Parents have an affirmative obligation to reinforce patriotic values and counter the narratives that are taught in school.

Get the Civitas Outlook daily digest, plus new research and events.