What Justifies Trump’s Intervention in Venezuela?

Unlike in the bipolar world, today the United States enjoys greater relative power, and international rivalry takes different forms. This helps explain the shift toward a more active strategy.

Editor's Note: This essay is part of our Venezuela Symposium.

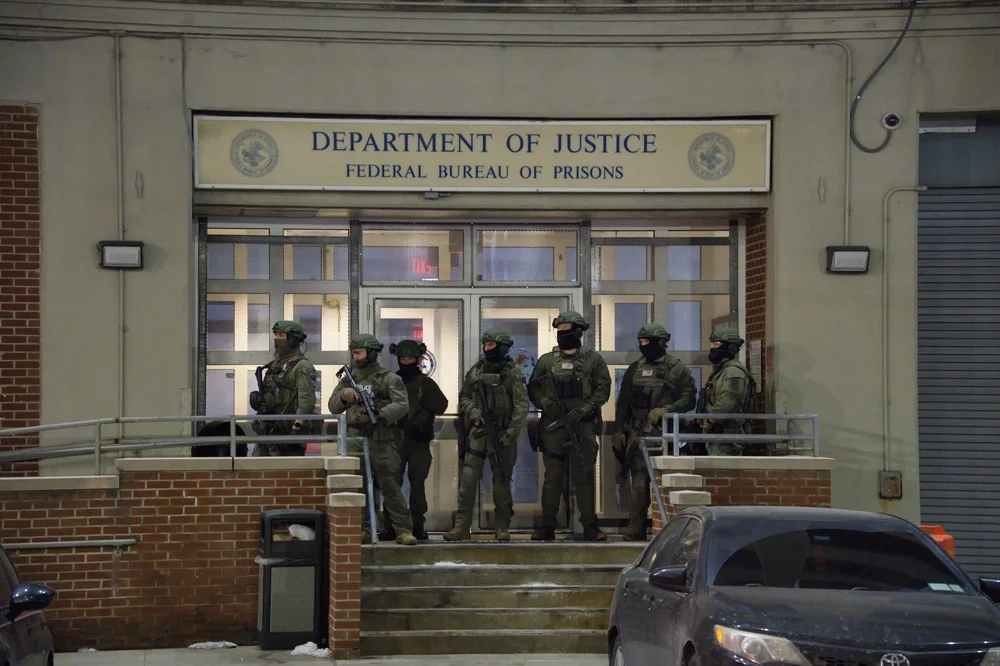

In November 2025, President Trump released the National Security Strategy of the United States of America. One of its central aims is to strengthen U.S. power, beginning with its immediate geographic environment in the American hemisphere. Trump’s policy toward Venezuela — and what has unfolded there in recent months — should therefore be read in light of that strategic framework. Two questions follow. First, is the diagnosis of Latin America correct? Second, are the proposed remedies and the steps now being taken, including intervention in Venezuela, also, correct?

For the Republican president, placing Latin America at the center of the agenda rests on two themes central to his political message. The first is immigration into the United States and the rise, or at least the perceived rise, of territorial insecurity associated with those migratory flows. The second is drug trafficking, which is driven primarily by the Colombia–Mexico corridor. Both dynamics, firmly rooted in U.S. domestic politics, translate into a negative externality that concerns American citizens and shapes the national security agenda.

The migration phenomenon, which has surged in both the United States and Europe, also points to a significant weakness in international law and global governance. In practice, the multilateral system has shown limited capacity to manage protracted political crises and to confront transnational illicit activity. More concretely, the United Nations has struggled to resolve conflicts and prevent institutional collapses that ultimately lead to mass migration, with direct effects on receiving states. In that context, migration is sometimes rightly, and sometimes through oversimplification, linked to drug trafficking and human trafficking. It is worth noting that such externalities rarely trouble dictatorships or authoritarian regimes, which tend to suppress them by force (as in China and Russia). The phenomenon is not new, but Europe’s Syrian crisis and the hemisphere’s Venezuelan crisis have accelerated public unease in prosperous liberal democracies.

Compounding these pressures is the growing antagonism of certain authoritarian powers toward the West. China, in its relationship with the United States, and Russia, in its relationship with Europe, have displayed increasingly hostile behavior and have learned to exploit the gray zones of the international order. At the same time, Europe has also contributed by action or omission to the erosion of the multilateral economic rules-based system: for example, it must periodically request from the WTO renewals or waivers for certain tariff regimes; in areas deemed “strategic,” para tariff measures have been adopted through regulatory channels; and, more recently, France has opposed free-trade agreements such as Mercosur, among other cases.

In China’s case, the opening pursued under President Jimmy Carter and led by Deng Xiaoping, an approach that began to take shape during President Nixon’s administration to prevent a Sino-Soviet alignment, facilitated China’s entry into global investment and trade flows. Yet for years, there have been allegations of technology appropriation, non-reciprocal restrictions on market access, and persistent regulatory asymmetries. From this vantage point, Trump’s critique of the way international law and the global economic order function is not easily dismissed.

In short, the Trump administration’s diagnosis is that international law, as it has operated over recent decades, is not working adequately. In light of the phenomena described, that diagnosis appears, in general terms, sound.

The remaining question is whether the measures adopted to address that diagnosis are themselves correct. To begin with, the strategy presented by Trump in November 2025 leans more toward intervention than toward containment, the posture the United States pursued for decades vis-à-vis the USSR. Containment, the dominant Cold War approach, avoided a direct attack on the Soviet Union and its proxies and instead focused on responding to advances against the West. It was a demanding strategy because the United States did not choose the battleground: it was not a matter of invading North Korea or striking the USSR, but of reacting when pro-Western governments were at risk

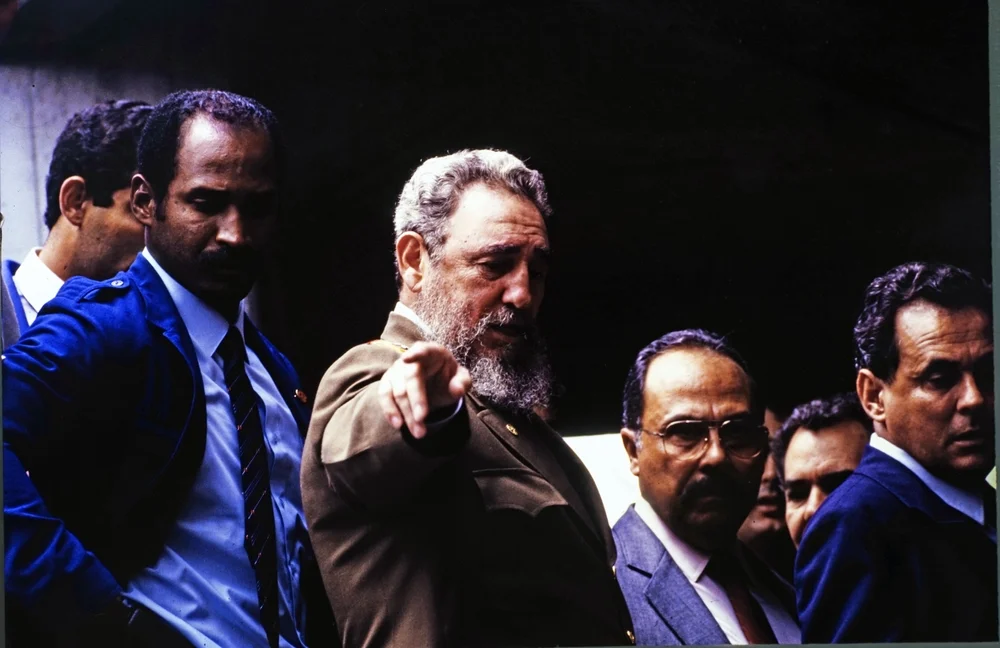

The current containment thesis would involve intervening only in cases where dictatorial regimes have not yet been consolidated. For example, intervention would be justified in a country where early signs of electoral fraud exist, as this could prevent the consolidation of such regimes. By contrast, in countries like Cuba or Venezuela, where the regimes are already consolidated, the United States would not intervene. Unlike in the bipolar world, today the United States enjoys greater relative power, and international rivalry takes different forms. This helps explain the shift toward a more active strategy. Even so, assessing its effects—its costs, risks, and benefits—requires evidence and time; it is therefore still too early to draw definitive conclusions.

Rodrigo Barcia Lehmann is a lawyer, PhD, and Master of Law and Economics. Research Professor, Universidad Autónoma de Chile. Member of BeLatin.

The Venezuela Symposium

Eight Latin American contributors discuss Venezuela's future and its wider consequences for the region.

Venezuela Post-Maduro

Indeed, for many, the Venezuelan situation seemed to have no other way out, since everything had already been tried without success. It was about time.

Donald Trump's New Hemispheric Policy

By adopting a more assertive foreign policy, the administration sought to reposition the United States at the center of the regional order.

Get the Civitas Outlook daily digest, plus new research and events.