Liberty and the Shackled Leviathan

The Leviathan of our era — any power capable of policing the world — must be shackled by multilateral law and genuine regional political organization.

Editor's Note: This essay is part of our Venezuela Symposium.

Liberty is rarely born of simplicity. It grows out of paradox, the constant, uneasy balance between a strong state and a strong society that mutually bind and push one another to behave, adapt, and deliver. In The Narrow Corridor (2019), Nobel Prize-winning economists Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson call this dynamic the path to a shackled Leviathan: a state powerful enough to provide order, public goods, and collective protection, yet constrained by organized citizens and robust institutions so it cannot prey upon them. Step out of this corridor, toward either a domineering state or a fragmented society, and liberty begins to wither.

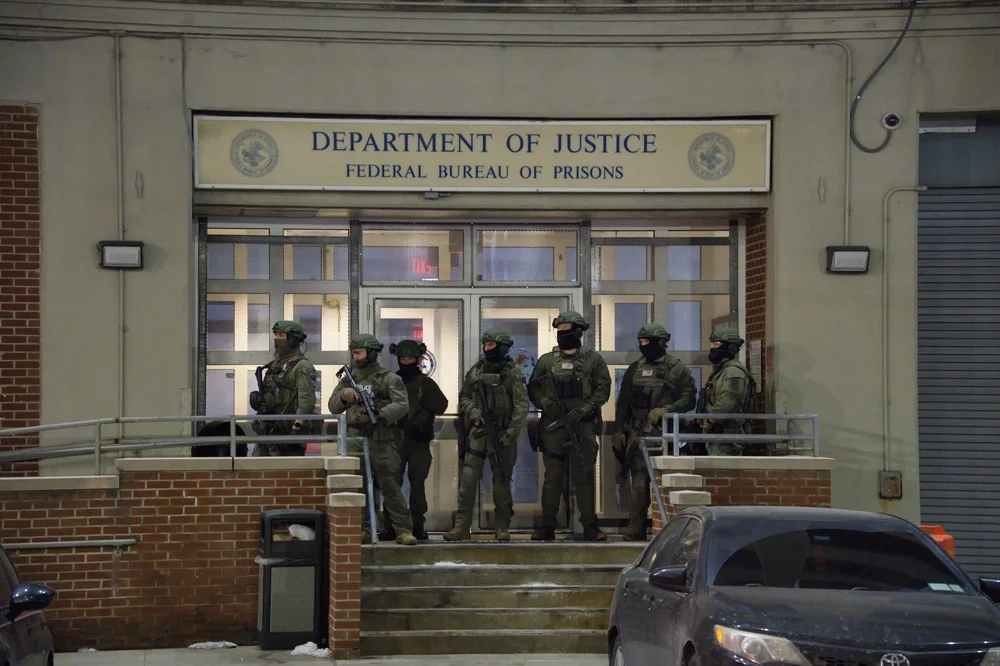

One of the most telling settings to explore this tension is the global system itself. In the contemporary world order, the United States Leviathan seeks to act as a de facto international policeman, with unchained military forces able to project power across commerce, technology, financial markets, law enforcement, oceans, and continents. In the metaphorical language Acemoglu and Robinson use, the United States has become “a true international sea monster” hybridized by its domestic checks and balances but unavoidably tempted by the prerogatives of scale: to patrol, to sanction, and, at times, to define what constitutes security and crime beyond its borders. From humanitarian operations to counternarcotics and counterterrorism efforts, the impulse to maintain order can be genuine. But it also raises the classic paradox in the Narrow Corridor: Who chains the Leviathan when it acts abroad with all its military power? Who can balance power in the global commons?

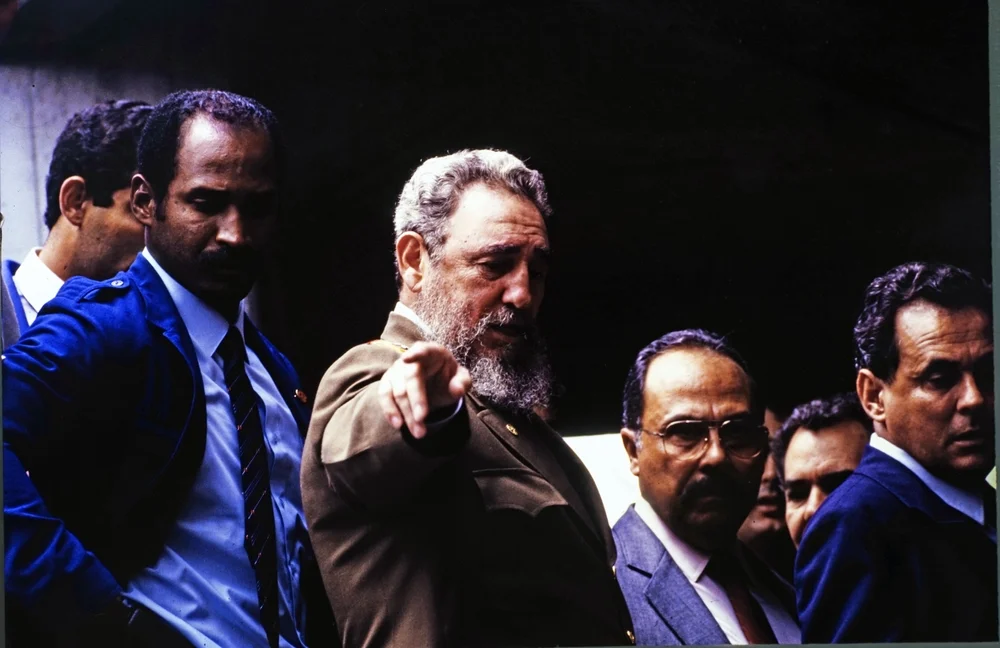

Declaring enemies, labeling adversaries, and deploying sanctions or force in the name of security can be necessary in response to real threats. History offers many examples of collective action against violent authoritarianism that prevented worse outcomes. Moreover, few dispute the harms inflicted by the Chávez-Maduro regime: political prisoners, censored media, exiles, dismantled checks and balances, economic collapse, and widespread violence. Ending these harms is morally compelling, but the means matter. If liberty requires constraints on power, international efforts must be lawful, proportional, and regionally legitimate. The corridor narrows when a single external actor unilaterally defines stakes and tools; it widens when Latin American states coordinate diplomatically, leverage regional institutions, and insist on sovereignty while deploying lawful instruments: sanctions, investigations, humanitarian corridors, and judicial cooperation.

Yet liberty is not only about what the state does; it is also about how power is constrained as it acts, and who gets to shape the rules. To restrain Leviathan, according to The Narrow Corridor, liberty needs both state capacity and popular mobilization. When a state acts as the world’s policeman, imposing its interests, such as controlling petroleum, oil, and lubricants (POL), global checks must apply. Multilateral law and cross-border cooperation should create a sphere of legitimacy to protect sovereignty.

However, while Trump orders a strike on Caracas to capture Maduro, he simultaneously directs the U.S. to withdraw from 66 international organizations, including 31 UN-affiliated entities, and treaties deemed contrary to U.S. interests. This sovereignty-focused review signals an effort to unchain the Leviathan internationally. Trump’s pledge to assume control over Venezuela and trade its oil for U.S. goods exemplifies an unconstrained Leviathan: concentrated power combined with the absence of effective countervailing institutions, overriding national autonomy and subordinating Venezuelan sovereignty to strategic imperatives. pressures that could extend to Colombia under the Petro government.

Latin America’s challenge is to build continental guardrails: institutions strong enough to resist authoritarian relapse yet inclusive of dissent, minorities, and local governance. Regional security must reflect principled autonomy, not satellite agendas. This is the groundwork for a Latin American balance of powers at the international level, extending Acemoglu and Robinson’s thesis into foreign policy. States must be strong enough to combat crime and authoritarianism, yet constrained by oversight, independent courts, and transparent multilateral mechanisms. Such architecture does not romanticize non-intervention; rather, it disciplines intervention by rooting it in law and reciprocal accountability.

The paradox of liberty is tangible: visible in every sanction, negotiation, and treaty that ties states’ hands so citizens can breathe. The Leviathan of our era — any power capable of policing the world — must be shackled by multilateral law and genuine regional political organization. Latin America must move beyond reaction toward a constructive equilibrium: sovereign and cooperative, yet firm against both authoritarianism and unconstrained state action, whether homegrown or imported.

Luis Antonio Orozco Castro is the President of the Colombian Association for the Advancement of Science (AvanCiencia) and a full professor at Universidad Externado de Colombia.

The Venezuela Symposium

Eight Latin American contributors discuss Venezuela's future and its wider consequences for the region.

Venezuela Post-Maduro

Indeed, for many, the Venezuelan situation seemed to have no other way out, since everything had already been tried without success. It was about time.

Donald Trump's New Hemispheric Policy

By adopting a more assertive foreign policy, the administration sought to reposition the United States at the center of the regional order.

Get the Civitas Outlook daily digest, plus new research and events.